2015 Open government: Toward a pan-canadian vision?

Don Lenihan

Senior Associate, Canada 2020

Suzanne Legault

Information Commissioner of Canada

August 2015

Contents

What is open government?

The idea of open government is as old as democracy itself, but it has evolved over time. While transparency and accountability have always been at the heart of these discussions, in the early days this was about providing citizens with the information they needed to prevent corruption and other forms of malfeasance. In those days, openness was mainly about ensuring a government’s integrity.

In more recent times, the focus has broadened. A few decades ago, new approaches to public management called on governments to start paying closer attention to outcomes. They challenged officials to state clearly the goals they were trying to achieve, gather information on their progress, and use it to measure and improve their performance. As a result, today open government is also about making available the information and data needed to assess a government’s effectiveness.

Now a third stage of open government is emerging. Countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom have built powerful open data websites and are using them to release massive amounts of government data on every topic imaginable—health, weather, traffic, trade, finances, and so on. This is charting yet another course for open government, based on three suppositions.

First, in the knowledge economy, data is the key to prosperity, much as natural resources were in the industrial economy. Data is the raw material from which new products and services will be fashioned. In releasing their massive data holdings to the public, governments hope businesses and others will use it to create wealth.

Second, this new resource is supposed to allow the public to track government’s actions and accomplishments with a depth and accuracy that was unthinkable two decades ago, thereby enhancing transparency and accountability.

Third, access to “Big Data” promises to move evidence-based policymaking and performance measurement (effectiveness) to a whole new level.

In sum, this third wave of open government is supposed to usher in a new era of prosperity and good governance. And perhaps it will, but if there is reason to be optimistic, there is also reason to be cautious. Flooding public space with government data won’t ensure prosperity, accountability or evidence-based decision-making, unless the commitment to Open Data is matched by equally firm commitments to two other streams of Open Government: Open Information and Open Dialogue. And on these, much work has yet to be done.

In 2012, the Government of Canada announced its intention to join the Open Government Partnership, an international movement of some 65 countries that have joined together to promote better governance through the innovative use of digital tools and the engagement of citizens. In this paper, we consider a few basic steps that must be taken by governments to ensure success. While the paper focuses on the Canadian context—and the Governments of Canada and Ontario, in particular—the main arguments are applicable to the Open Government movement, generally.

Open government in Canada

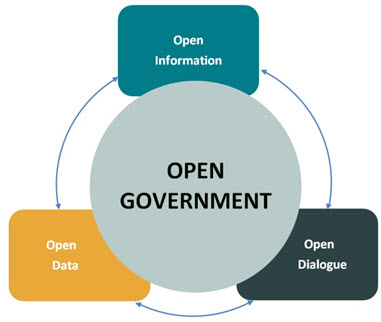

Based on our research, the Open Government discussion in Canada differs from that of many other countries in that it explicitly defines Open Government through three streams of activity: Open Data, Open Information, and Open Dialogue. While all three streams are present in the Open Government Partnership’s (OGP) definition of Open Government, most countries do not usually separate them out from one another so clearly. As we hope to show, doing so is helpful.

Open Data calls on governments to make their data holdings available to the public. Open Information calls on them to advance proactive disclosure and freedom of information. Open Dialogue tells them to engage the public more directly in the policy process.

Together, these three streams inform and support one another and, when integrated, work towards the goals of Open Government. For the purposes of this paper, the interaction between the three streams can be represented as follows:

Text version

This diagram illustrates the interactions between the three streams of Open Government: Open Data, Open Information, and Open Dialogue. The words "Open Government" are in a large circle in the centre of the diagram. The three streams surround the circle and are connected to each other with arrows.

Generally, these streams can be identified through their relatively distinct communities of practitioners, each with its own history, interests and skills:

- Open Data attracts individuals and organizations with expertise in digital technology and its capacity to collect, share and integrate huge amounts of data.

- Open Information is the cornerstone of transparent and accountable government, from proactive disclosure to FOI legislation and freedom of the press. It is especially important to journalists, political activists and policy advocates.

- Open Dialogue is part of a long tradition of citizen and community engagement and calls for greater public involvement in policymaking, especially through digital tools.

As open government progresses in Canada, it is becoming increasingly clear that these three streams are viewed by government as largely independent of one another. If Open Government is to succeed, it requires an integrated approach, where the knowledge and skills from all three communities are pooled together to accomplish open government commitments that draw on all three streams. If the digital age presents an opportunity to renew or transform governance, it won’t be accomplished by technologists and analysts alone—the “Open Data crowd”—meeting open data commitments. Equal effort also needs to be put toward open information and open dialogue commitments, enlisting journalists, political strategists, facilitators and community activists in the process. So what does this involve?

The two action plans

The Government of Canada launched its first Open Government Action Plan in 2011.Footnote 1 Although it identified all three streams and contained important initiatives on Open Data, the section on Open Information included only minor steps to change how the Access to Information Act is administered, such as allowing access to information requests to be filed and paid online. As for increasing its scope, the most ambitious commitment was to remove a few restrictions on some historic documents held by Library and Archives Canada.

The Open Dialogue section was similarly lacking in ambition. It contained no provisions to engage civil society or citizens on issues around information, let alone to open up the policy process. The few consultations that did occur focused mainly on Open Data.

An independent evaluation of the Plan in 2012 confirmed the obvious. Canada’s Open Government initiative was really about Open Data. The reviewer urged the government to use its next plan to expand its focus beyond Open Data and to take steps to improve access to information and engage citizens in a more meaningful and regular way.Footnote 2

When the second plan was released in 2014, it sounded more encouraging. The Plan pledges “to expand its open government activities to include a wide-ranging set of initiatives on open information and open dialogue…”Footnote 3 To its credit, the Plan is articulate and clear about the interdependence of the three streams. Open Dialogue, it says, begins by enhancing the availability of data and information to inform active civic participation. It matures when citizens and civil society organizations are empowered to voice their insights and opinions, and when governments demonstrate their willingness to meaningfully incorporate that public feedback as part of decision-making processes.Footnote 4

Toward this end, the Action Plan promises to achieve what it calls “next generation consulting.” Specifically, “…the Government of Canada will develop new and innovative approaches and solutions to enable Canadians to more easily take part in federal consultations of interest to them. The government will also develop a set of principles and procedures to guide consultation processes in order to increase the consistency and effectiveness of public consultations across government. As a result, Canadians will be more aware of the opportunities to engage with their government, will have consistent, advance notice of government consultations, and will have access to easy-to-use solutions for providing their ideas on federal programs and services.”

In terms of open information, the Action Plan commits to expand the proactive release of information on government activities, programs, policies, and services, with the goal of making information easier to find, access, and use. It also contains a number of deliverables related to the Access to Information Act, however, again these focus on the administration of the Act. Both action plans ignored recommendations from the federal Information Commissioner to, among other things, reform the Access to Information Act.

Finally, the plan is anchored in the government’s new Directive on Open Government,Footnote 5 which requires federal institutions to release proactively a maximum amount of data and information in an open format. According to the government, the long-range goal of the Directive is to create a culture of “open by default” across the three streams, that is, that the government comes to see the approach it has already taken for Open Data as the norm and proactively releases information of all sorts in an open format.Footnote 6

Overall, the vision of Open Government in the Action Plan—and, especially, the idea of a culture of open by default—is laudable and ambitious, but before we conclude that the Plan constitutes a big step forward on Open Dialogue and Open Information, we should look more carefully. In fact, the actual commitments to action fall far short of these aspirations. To see why and what really needs to be done to establish a culture of open by default, let’s take a closer look at both streams, beginning with information.

Open information and the Access to Information Act

Canada’s Information Commissioner recently released a report containing recommendations to renew Canada’s Access to Information Act.Footnote 7 In the report, it is explained that Canadians’ society and expectations surrounding information have changed, but that government has failed to keep pace with the times. While the basic principles behind the Act remain sound, it badly needs to be modernized.

The need to modernize the Act becomes all the more urgent in the face of open government. This is because, in its present state, the Access to Information Act is an impediment to open government. The exemptions in the Act are a how-to guide for preventing disclosure and the Act does little to encourage proactive disclosure, timely responses or the release of information in open formats. In the words of the Commissioner, “The Act is applied to encourage a culture of delay…deny disclosure [and act] as a shield against transparency.”Footnote 8

The exemptions and exclusions in the Act for the decision-making process of the government are good examples of how the Act is an impediment to open government. Definitions are too broad, periods of protection are too long, there is no assessment of harm in disclosure, and there is no public interest override.

For example, the Act allows advice or recommendations developed by or for a government institution or a minister of the Crown to be withheld from disclosure. A protection like this exists in many freedom of information laws around the world to allow for the provision of full and frank advice. However, the broad language in the Act used for this protection allows significant amounts of information about the policy and decision-making process to be withheld from disclosure, far beyond what must be withheld to protect the provision of free and open advice.

Citizen engagement underpins all aspects of open government and is a vital link between transparency and accountability. If the Act continues to protect the decision-making process in the way it currently does, it will continue to thwart citizen engagement.

The out-dated Access to Information Act will also cause problems for the implementation of open government activities the government has committed to undertake. For example, the Directive on Open Government is “subject to applicable restrictions associated with privacy, confidentiality, and security.”Footnote 9 [emphasis added] The Access to Information Act will undoubtedly limit what can be disclosed under the Directive in ways that are contrary to open government.

The open information deliverables, which focus on improving the administration of the Act, are similarly deficient. Improving the administration of an act with fundamental flaws will do very little to meaningfully advance open government objectives.Footnote 10

There is a tension between the open by default culture the government’s open government plan is anchored in and the overly-restrictive legal framework for accessing information that currently exists. The two cannot co-exist for long if the goals of open government are to be achieved.

It is our belief that the culture of openness can prevail and the basic strategy to achieve this is simple and clear. The principle of Open by Default must be extended beyond data to include information and dialogue. Although the government’s Action Plan aspires to this, its commitments fall far short of the mark. On information, the Information Commissioner’s submissions to the government during consultation on its action plans and her report to renew the Act show us just how far.

The Information Commissioner made two submissions during the consultation phase for the second national Action Plan. The first, which was submitted while ideas for the plan were still being generated, recommended that the plan include a commitment to modernize the Access to Information Act.Footnote 11

After the draft action plan was posted for comments, the Information Commissioner made a second submission with 16 specific recommendations to improve the plan.Footnote 12 In addition to stressing again that modernizing the Access to Information Act is essential to meet open government objectives, she also made several other recommendations intended to achieve an integrated approach to open government, such as:

- that the government provide training to ensure that all government employees under the Access to Information Act interpret the Act in favour of maximum disclosure;

- that the government release records to access to information requesters in accordance with the principles of Open Government;

- that the government work with other governments at all levels to link their access to information systems together and allow for centralized searches;

- that the government commit to increasing compliance with the Access to Information Act by setting specific performance targets to improve timeliness; and

- that the government create an open government lens to be used in the design and implementation of policies, programs, initiatives and legislative proposals.

The Commissioner’s report to modernize the Access to Information Act contains 85 recommendations, with an overarching goal to establish a better balance between the public’s right to access and the legitimate protection of sensitive information. These recommendations would serve to maximize disclosure in line with a culture of open by default. For instance, the Commissioner recommended that:

- Exemptions to the right of access should be narrowed so that they protect only what requires protection. This will lead to the maximum amount of information being disclosed where possible.

- The government should proactively publish information that is clearly of public interest.

- While the Act currently contains limited public interest overrides that are applicable to only a few sections of the Act, a general public interest override should be inserted into the Act and made applicable to all exemptions. When deciding whether disclosure is in the public interest, the government should be obliged by the Act to assess this against the principles of Open Government.

- The obligation on institutions to provide records in open, reusable, and accessible formats should be strengthened.

The call to modernize the Access to Information Act is not just about making information easier to get or more convenient. It is about raising the quality of democratic participation and government accountability to a new level by aligning the Act more closely with the practices and values of open government.

This view is shared by Information and Privacy Commissioners across the country,Footnote 13 who in 2010 issued a Joint Resolution calling on their respective governments to declare the importance of Open Government for Canadians and to foster a culture conducive to it.Footnote 14

To understand how the commissioners’ support for Open Information and Open Data can enhance democratic participation, we must turn to the work, expertise and experience of those in the citizen-engagement community, which brings us to Open Dialogue.

Open dialogue in Ontario

Ontario is Canada’s most populous province and the home of its second largest government. In October 2013, Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne announced a nine-person panel of experts to undertake a province-wide consultation and research process to develop recommendations to make Ontario “the most open and transparent government in the country.”Footnote 15

While Ontario adopted the federal model of the three streams of Open Data, Open Information and Open Dialogue, it added an interesting twist. The government recognized that much good work had already been done on Open Data and felt there was no point in “reinventing the wheel.” Instead, the panel was asked to invest a majority of its time thinking through what the government saw as a new and emerging set of issues around open dialogue.

Now, while Open Dialogue is obviously about giving participants a say in the policy process, the government recognized that this can range from an opportunity to express a view to having the authority to veto or make important choices, with other options in between. In short, different types of dialogue processes involve different degrees of public participation; and, presumably, different ones are suited for different purposes.

If so, reasoned the government, there should be a principled and systematic way of designing dialogue processes to choose the right form, ensure the process is appropriately designed, and use events or digital tools effectively to achieve the objectives. This idea of a principled approach was central to the panel’s discussions and the recommendations in its final report, Open by Default.Footnote 16

In particular, Recommendation 1-1 b) calls on the Ontario government to launch a series of demonstration projects to test and explore the different forms of dialogue and engagement; and to systematize the learning into a policy framework that can guide the development of open dialogue processes for the government as a whole.

The Hon. Deb Matthews, Deputy Premier of Ontario and Minister for Open Government, recently confirmed that the government will launch such a project by the end of 2015. According to Matthews, the Wynne government is ready to take “an important step toward Open Dialogue with the development of a public engagement framework…We will also launch a series of demonstration projects…to engage Ontarians in how to move forward on some of our core priorities.”Footnote 17

Building an open dialogue framework

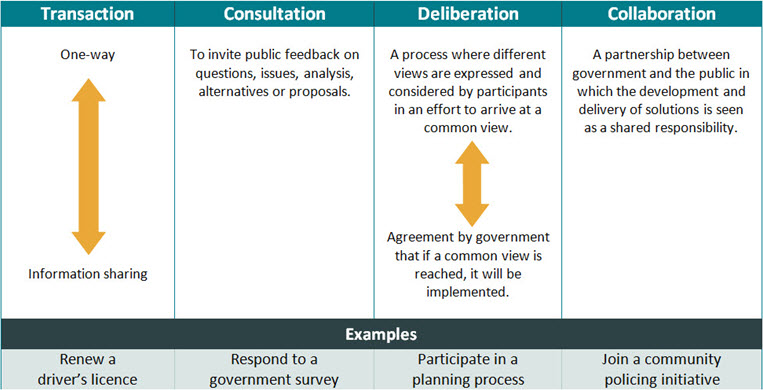

In fact, much work on the foundations of such a framework has already been done and, based on this, the Ontario government’s expert panel recognized four distinct kinds of dialogue processes:Footnote 18

Text version

This table illustrates four kinds of dialogue processes: transaction, consultation, deliberation and collaboration.

The first column shows the transaction process. A double sided arrow is placed between the words "One-way" and "Information sharing." An example given is to renew a driver's licence.

The second column shows the consultation process. It is defined as: To invite public feedback on questions, issues, analysis, alternatives or proposals. An example given is to respond to a government survey.

The third column shows the deliberation process. A double sided arrow is placed between the following two sentences: "A proccess where different views are expressed and considered by participants in an effort to arrive at a common view." and "Agreement by government that if a common view is reached, it will be implemented." An example given is to participate in a planning process.

The fourth column shows the collaboration process. It is defined as: A partnership between government and the public in which the development and delivery of solutions is seen as a shared responsibility. An example given is to join a community policing initiative.

- Transactions: A transaction is a one-way relationship in which government delivers something to the public. Where engagement is involved, this is usually information, but one could also speak of engaging the public through public services that deliver other goods, such as a permission (license), an object (drugs) or a service (policing).

- Consultation: Consultation provides members of the public with an opportunity to present their views on a subject to public officials. The process ensures they have a chance to make their views known to government. Once they have done so, the officials retreat behind closed doors to review the arguments, weigh evidence, set priorities, make compromises and propose solutions. Their conclusions are then presented to the government, which makes the final decisions.

- Deliberation: Deliberation allows participants to express their views, but it also gets them to engage one another (and possibly government) in the search for common ground. Whereas consultation assigns the task of weighing evidence, setting priorities, making compromises and proposing solutions to officials, Deliberation brings the participants into this process.Footnote 19

- Collaboration: Collaboration involves sharing responsibility for the development of solutions AND the delivery or implementation of those solutions. A government shares these responsibilities when it agrees to act as an equal partner with citizens and/or stakeholders to form and deliver a collaborative plan to solve an issue or advance a goal.

So the motivating idea behind Ontario’s Open Dialogue initiative is, first, that there are different kinds of engagement processes; and, second, that choosing the right one for the task at hand is crucial to success. Many governments still rely almost exclusively on only two of these: information sessions and consultation.

This worked well enough in the past, but in the digital era it is no longer adequate. Societies like Canada are now highly connected and, as a result, issues, organizations and outcomes are linked in new and often surprising ways. As officials explore the implications for policymaking, decision-making can get very complex very quickly.

Consultation is ill-suited to this environment precisely because the key choices get made behind closed doors. But in many policy issues, there are just too many factors at play, too many trade-offs that have to be made, too many ways that things could be done differently, to explain to citizens after the fact why government made the choices it did. Those who disagree with those choices are often left feeling that the whole process is arbitrary or, worse, that it was rigged from the start.

By contrast, conducting more of these discussions out in the open would allow the public to see how decisions are made in this new environment and to participate more fully in them. Far from undermining good governance, Open Dialogue can make a major contribution to it by ensuring transparency and inclusiveness, which, in turn, creates clarity and gives people a sense of ownership of the decisions.

Open Dialogue can also increase effectiveness. Citizens and stakeholders bring a wealth of experience to the table that can help a government assess how different options will impact on people and communities, which, in turn, leads to better decisions.

Finally, in Open Dialogue processes appropriate information and data must be accessible to the public so that options can be publicly weighed against the evidence, which promotes evidence-based decisions.

In sum, Ontario’s proposed Framework will provide the government with a toolbox that contains all four types of processes, along with a set of instructions on how to choose and design the right process for the issue at hand. This, in turn, will promote Open Government goals on prosperity, transparency and accountability, and evidence-based decision-making.Footnote 20

By contrast, the federal government’s second Action Plan seems to be anchored in the past. There is no acknowledgement of the complex structure of dialogue; and it makes no mention of the kind of deliberation, shared decision-making or deep collaboration that Ontario recognizes as central to Open Dialogue.

Judging from the language, the federal focus still seems limited to information sessions and consultation. If so, its goal of providing “next generation consultation” is likely to disappoint. In the end, it will be more about automating existing practices—putting old wine in new bottles—than using the tools and the expectations to transform dialogue for the digital age.

Toward a pan-canadian vision of open government

For at least three decades, reformers have been calling on governments to “transform” themselves. They have told officials to blow up the silos, reduce red tape, streamline processes, build new networked infrastructure, share information better, and to become flatter and more flexible, integrated and collaborative. Yet in spite of huge investments in digital technologies and endless experiments with new management tools and techniques, the silos and government hierarchy remain intact. Governments have proven remarkably resistant to these efforts at change.

The reason is clear. Real transformation requires real culture change and that takes more than new systems and management tools. Organizational culture is a product of the attitudes, values and practices of the people behind the systems and the tools—the skills and ingenuity they use to make them work or not work. Culture change is about mobilizing these people around new ideas that have the power to change how they see and use the tools at their disposal.

Open Government is a fountain of brilliant new ideas, systems and organizational forms. We’ve only begun to dip into it. But to make these new forms really work—to use them to transform governance—we need the right people behind them, and using them the right way. The three streams are the key to this. Success depends on merging these streams and enlisting the diversity of skills, experience and expertise within each community.

To its credit, the movement has now engaged a significant cross-section of the policy community through Open Data, but recruitment can’t stop there. If the digital revolution is an unparalleled opportunity to promote prosperity, transparency and accountability, and evidence-based decision-making, success won’t be accomplished by technologists and analysts alone. The movement needs journalists, political strategists, facilitators and community activists. The challenge now is to mobilize and unite these groups around a shared vision of Open Government.

Open by Default is the rallying cry that could mobilize and unite the whole community. Canadian governments could be on the forefront by defining a pan-Canadian vision of Open Government that extends this principle to Open Information and Open Dialogue. We already know a lot about what this involves:

- Regarding Open Information, the first step is to modernize the Access to Information Act so that the open information legal framework is aligned with, rather than contrary to, open government. Following the principles embedded within a modernized Act is the next step. Commitment and leadership on implementation should come from the top.

- Regarding Open Dialogue, we’ve seen that policy processes are complex and diverse. Real progress on Open by Default here means, first, that the choice and design of the policy process must be principled rather than ad hoc; and, second, where appropriate the deliberations unfold in public through a properly designed engagement process. Ontario’s work on a public engagement framework could provide the model for this.

Unfortunately, an outdated access act that can be used as a shield against transparency threatens to take the government in a very different direction. Something has to give. Open Government cannot co-exist with the Act for long. The tension is too great; the irony too obvious.

We believe the principle of Open by Default is the key to reversing this trend. While there is a long way to go, the good news is that, in the context of Open Data, the principle has been officially recognized and adopted by many governments around the world. Extending it to Open Information and Open Dialogue is a natural and logical step and, as we have seen, Canadians have a pretty clear idea how to do it. This would move the yardsticks on culture change a long way. Canadians are ready for this, but first we need clear evidence of a clear commitment to the concept from our political leaders.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

‘The Canada Action Plan on Open Government 2012-2014’ is available at: http://www.opengovpartnership.org/country/canada/action-plan

- Footnote 2

-

See ‘Independent Review Mechanism, Open Government Partnership,’ http://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/Canada_final_2012_Eng.pdf

- Footnote 3

-

‘Canada Action Plan on Open Government 2014-2016,’ http://open.canada.ca/en/content/canadas-action-plan-open-government-2014-16.

- Footnote 4

-

Ibid: D. Open Dialogue – Consult, Engage, Empower

- Footnote 5

-

The Directive is a mandatory policy requiring federal government departments and agencies to maximize the release of data and information of business value subject to applicable restrictions related to privacy, confidentiality and security. Eligible data and information will be released in standardized, open formats, free of charge. Treasury Board Secretariat, 2014, http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=28108

- Footnote 6

-

‘Canada’s Directive on Open Government – Creating a Culture of Open by Default,’ http://open.canada.ca/en/Canada%E2%80%99s_Directive_on_Open_Government_%E2%80%93_Creating_a_Culture_of_%E2%80%9COpen_by_Default%E2%80%9D

- Footnote 7

-

‘Striking the Right Balance for Transparency – Recommendations to modernize the Access to Information Act,’ Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, March 2015, http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/eng/rapport-de-modernisation-modernization-report.aspx

- Footnote 8

-

Ibid: Commissioner’s message.

- Footnote 9

-

Supra note 6: 5.1 Objective.

- Footnote 10

-

There are other problems with the open information commitments in addition to being based on the outdated Access to Information Act. Many of the deliverables related to the administration of the Act are not new activities. For example, the government committed in its plan to publish statistical information on extensions and consultations related to access requests. However, this information is already tracked and reported on the government’s Infosource website (http://www.infosource.gc.ca/bulletin/bulletin-eng.asp). Additional statistics on extension times, including the length of time for consultations, were added to Infosource in 2002-2003. Further statistics on consultations were added in 2011-2012.

- Footnote 11

-

‘Letter to the President of the Treasury Board on the Government's consultation on Action Plan 2.0 for the Open Government Partnership Initiative,’ Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, September 2014, http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/eng/autres-documents-other-documents-2.aspx

- Footnote 12

-

‘Letter to the President of the Treasury Board on Action Plan 2.0,’ Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, November 2014, http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/eng/lettre-plan-d-action-2.0_letter-action-plan-2.0.aspx

- Footnote 13

-

Canada is a federal state with 10 provinces, three territories and a national government.

- Footnote 14

-

See ‘Open Government: Resolution of Canada’s Access to Information and Privacy Commissioners, September 1, 2010 – Whitehorse, Yukon’: http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr-ori-ari_2010_1.aspx

- Footnote 15

-

This panel was chaired by Don Lenihan.

- Footnote 16

-

The report is available at: https://dr6j45jk9xcmk.cloudfront.net/documents/2428/open-by-default-2.pdf

- Footnote 17

-

See ‘Canada 2020 Open Government Forward,’ by the Hon. Deb Matthews, in Setting the New Progressive Agenda, forthcoming in June 2015 from Canada 2020 at www.Canada2020.ca

- Footnote 18

-

The framework is also discussed in “Rebuilding Public Trust: Open Government and Open Dialogue in the Government of Canada,” by Dr. Don Lenihan and Dr. Carolyn Bennett, MP, April 2015, Canada 2020, available at: http://canada2020.ca/open-government-open-dialogue-lenihan-bennett/

- Footnote 19

-

There is also an aspect of “depth” to this kind of participation, which is represented by the two-way arrows in the diagram. Depth refers to how far the public’s role in the deliberation stage is intended to go. For example, it might be limited to providing a first draft of a list of goals for a strategy. Alternatively, government could ask the participants to push the discussion as far as they can, possibly even promising them that if they reach full agreement on a decision or a plan, it will abide by their decision. And there are many degrees in between.

- Footnote 20

-

Nothing here suggests that every government decision requires public engagement. Many do not and should continue to be made behind closed doors by Cabinet. The Framework not only provides criteria for choosing a process, but for deciding when an issue requires public engagement.